|

| From Drop Box |

Monday, September 15, 2008

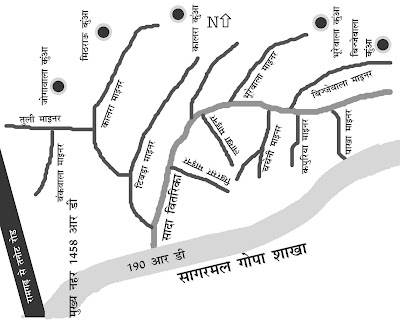

The bizarre network of ignp canal

Monday, September 8, 2008

Making Participatory Irrigation Management operational in IGNP Stage II

The Indira Gandhi Canal (IGNP), one of the biggest canal networks in the world, represents the largest ‘public investment’ by the post-colonial developmental State in the state of Rajasthan. It is proposed to offer solutions to many important and long standing developmental challenges of the Thar. IGNP is not only the largest irrigation scheme in the state of Rajasthan but it is also one of the first Command Area projects in

Some of the key local issues that make the case of the IGNP Stage II ‘specific’ in the national discourse on PIM are the unresolved problems related to the settlement of communities from heterogeneous socio-economic and cultural backgrounds; recognition of and provisions of basic amenities in the chak abadis; issues concerning sustainable ecological practices regarding land and water use; integration of livelihoods based on agriculture and livestock rearing; need for the diversification of non-farm livelihoods and introduction of new vocational skills; crisis of representation and efficacy of a range of formal and informal CBOs (Community Based Organisations) vis-à-vis the local Panchayats.

It is our submission that there is need to take into consideration the specificity of the IGNP Stage II to outline a workable and participatory concept of PIM. The current impasse has to give way to a concept of PIM that moves away from the ‘conventional notion’ of only limiting itself to institutional changes in water delivery and distribution, O&M of canal networks combined with the rehabilitation of the infrastructure.

Given the specificities of the local reality of the command area of the IGNP Stage II, to make the concept operational it would be meaningful to address issues of settlement of the settlers as well recognition of the chak abadis, equity, and ecological sustainability in a comprehensive and integrated manner.

The concept of PIM was officially adopted by the state of Rajasthan after 1995, and a Bill to this effect was issued in 1999. PIM has finally got a legal backing in the form of the Rajasthan Farmers’ Participation in Management of Irrigation Systems Act 2000 (followed by Rules 2002). However the field reality of the command area of Stage II has been such that so far the IGNP bureaucracy has evaded talking about PIM in an upfront manner.

PIM was introduced in these areas as a broad ranging concept with irrigation management as the central but not the only issue. The move by the CADA in 1996 to constitute Nahari Kshetra Vikas Evam Prabandhan Samiti (NKVS) as registered societies gave the command area settlers an opportunity to constitute their own institutions to work towards not only participatory irrigation management but ‘integrated development’ of their chaks and chak abadis as well. In a span of one and a half year around 82 such NKVS were registered in Stage II. This was a recognition of the fact that there were many problems relating to ‘settlement’ that were pending before participatory irrigation management by farmers could realistically take off.

This was a recognition of the fact that there were many problems relating to ‘settlement’ that were pending before participatory irrigation management by farmers could realistically take off.

The NKVS were intended as popular elected bodies of allotee farmers having a legal existence either as a registered society, a joint stock company or a cooperative. They were user associations to be responsible for the management of the micro networks of the IGNP canal. As peoples’ institutions they were projected as a solution both to the corruption and callousness of the lower bureaucracy and the profiteering of the contractors. In fact ‘participation’ and ‘popular institutions’ became buzz words resounding in almost any important gathering about the project.

But the enthusiasm of the higher officials of the CADA was marred by the conservative attitudes of the lower bureaucracy that was resistant to change and wanted to function in much the old fashion. As a consequence not much could take off on the ground despite the fact that the NKVS on paper continue to have a mandate for ‘integrated development’. Even in the recent development programmes of CADA supported by the WFP, an agency that has been supporting the cause of settlement motivation in the Stage II for almost a decade now, the NKVS despite having the mandate and the legal legitimacy have been bypassed in the favor of a handful of NGOs.

Ever since the passing of the PIM Act of 2000, there has been confusion within the different IGNP Departments, mainly Irrigation & CADA about whose responsibility promotion of PIM really is. In this vacillating discourse on PIM in IGNP Stage II, farmers and chak Samites are caught between the officials of these two departments, who are themselves not very clear about how to further the process of promotion of PIM

A holistic and locally specific concept of PIM has to emerge from below, with the genuine participation of the farmers in ‘policy formulation and not just implementation’. PIM should not limit itself to be only a ‘prescription from the top’. While adhering to the broad framework outlined by the Rajasthan PIM Act 2000 and Rules 2002, we feel there is ample scope to come up with appropriate concepts of farmers’ institutions for the IGNP Stage II area.

And the processes of participatory policy formulation for PIM would be greatly energized with the active participation of civil society. This entails initiating processes of consultation / participation of the farmers in exploring the appropriate concepts of PIM most suited for the IGNP Stage II with not just mediations from grass-root NGOs but also by forging robust linkages with other civil society actors, both inside as well as outside the region.

Presentation in the CADA office in

(This note primarily draws upon the experience of a team of NGO workers and community members who have been involved, since last few years, in addressing issues relating to land, water and livelihood rights of settlers (farmers and pastoralists) of the IGNP Stage II Command area, mostly in Pugal and Kolayat area of Phase I and Ramgarh area of Phase II.)

Sunday, September 7, 2008

Whither Harikke

tlej or Beas, both of which would anyway end up in gigantic dams, Pong or Bhakhra, in the middle Himalayas. If you still want to go upstream it is advised that you travel with a back pack, preferably along the Sutlej because that would lead you to the highest freshwater lake in the world, the Mansarovar. For such has become the pattern of water courses in modern India; such has been the scale and magnitude of river course re-direction in the modern including the colonial and post colonial times.

tlej or Beas, both of which would anyway end up in gigantic dams, Pong or Bhakhra, in the middle Himalayas. If you still want to go upstream it is advised that you travel with a back pack, preferably along the Sutlej because that would lead you to the highest freshwater lake in the world, the Mansarovar. For such has become the pattern of water courses in modern India; such has been the scale and magnitude of river course re-direction in the modern including the colonial and post colonial times.We went by jeep, keeping saner counsels in mind, and tracked the main course of the IGNP in the command area towards the naali and Stage I area, coinciding with significant transhumant trails, then through Bhakra minors and the 75 year old Gang canal with its degraded command and minors into the Eastern canal, Sirhind, and the RCP surrounded by lush greenery, before reaching the barrage that get its name from the Harikke patan in Punjab. Whether or not you marvel at the amazing architectural layout on pure deset areas running on hydraulic principles, the reasons for the construction are pretty straightforward. The Harikke Barrage was mainly conceived in the 1940s in the Rorkee School of Civil Engineering by the then Chief Engineer of the erstwhile Bikaner state, Kanwar Sain. He was also involved in the construction of the Gang Canal which flowed from the pre- Harikke time from the Husainiwala Barrage in Ferozpur, Punjab, constructed in the early 1920;’;s across the Sutlej. The main reason for the need for the construction of the Harikke Barrage, as he proffered to Nehru, was that since the Indo-Pak boundary / frontier line cut longitudinally cut through the river Sutlej, this provided scope for the Pakistan for cutting canals from their end of the river bank, thereby reducing the water level discharge and depriving the Gang Canal of much needed water. Apart from this pure geo political consideration he add

ed a good deal of moral missionary zeal to ‘green the desert’ without taking into consideration any of its possible impacts and its ecological assessments. ‘Greening the desert’ was a moral missionary slogan, under the guise of which systematic and irreversible assaults on various ecosystems were carried out. Nehru, to be fair, was skeptical of the RCP project. But when World Bank pressure was brought to bear on his government, he yielded and then eventually joined the moral missionary bandwagon, bombastically talking about ‘temples of modern India’.

ed a good deal of moral missionary zeal to ‘green the desert’ without taking into consideration any of its possible impacts and its ecological assessments. ‘Greening the desert’ was a moral missionary slogan, under the guise of which systematic and irreversible assaults on various ecosystems were carried out. Nehru, to be fair, was skeptical of the RCP project. But when World Bank pressure was brought to bear on his government, he yielded and then eventually joined the moral missionary bandwagon, bombastically talking about ‘temples of modern India’.As India and Pakistan started developing new uses of waters of the Indus river basins tensions mounted between the two countries. The matter was discussed at various levels and it was in March, 1952 that Indian and Pakistan finally agreed to accept the good offices of the World Bank for resolution of the dispute on sharing the Indus waters. The World Bank while considering distribution took into account the various possibilities of uses of this water in India and Paksitan. While the work on the project was in progress, thanks to the good offices of the World Bank, the Indus Water Treaty was signed at Karachi on September 19, 1960, between India and Pakistan, after eight years of torturous negotiations. All through the deleibeartions , the rajasthan canakl was the kingpin of India’s case. Emphasizing the crucial importance of the rajasthan Canal in India’s economy….Nehru wrote to the president of the World bank in a letter dated July 11, 1960 that:

“Rajasthan canal is of vital importance to us and that our planning is based on it (italics mine). There is a yearning all over the area served by the rajasthan Canal for water and any delay in providing adequate supplies of water to this canal would create very difficult political social and economic problems for us…”

Viewing the canal as the kingpin of state planning was an ideological difference Nehru wanted to posit against the colonial / WB gaze. Nehru did not live long enough to do a reality check. In fact, more than 40 years after, even the World Bank has not bothered to carry out any reality check of its own either, their main interests having withered by the end of eighties when the writing got too big o the wall to be ignored.

We are not here to lament or indulge in counter sloganeering against big dams, barrages, etc. For the World Bank, what is clear is the incredible size of the increasing ‘wastelands’, measurable in terms of degraded commons, produced as a consequence of its own interventions; but what is astounding, for any branch of disinterested scholarship is the rapidity of degradation, in this case a real tragedy of the commons, through large scale privatization, the sheer speed of eco-catastrophies and the resulting chaos that has already occurred. This can only be seen once we are in the intricate canal network, the delivery points of the main canal, or the end use hardware points so to speak. Other than private transformation of public resources (mostly in concrete and cement), everything else, minors, sub minors the end use channels many lie in ruins. But besides the ruination that it has produced upon itself, through methodologies designed for yielding, escalating yet exact calculations in the beautiful language of mathematics, wha

t is really tragic is the waste that the canal has wrought upon commons, pastures, rangelands, their bio diversity, traditional dry land farming practices combined with intricate use of rain water harvesting structures, and so on. Increasing desertification is not the nightmare; it is the increasing laying waste of nature that is.

t is really tragic is the waste that the canal has wrought upon commons, pastures, rangelands, their bio diversity, traditional dry land farming practices combined with intricate use of rain water harvesting structures, and so on. Increasing desertification is not the nightmare; it is the increasing laying waste of nature that is.Finally, let us come to the crux of the matter, the string that holds together all the pieces that is, water. Everything that we have been talking about everything that happens on the region stretching from river valleys of Punjab to the snowlines of Himalayas to the rainshadow area and the extreme arid western zone of Rajasthan is related to a specific spread and districution of ewater. It is more with regard to this resource rather than land that makes the difference between the nature of real capitalist intervention and those undertaken only in the previous historical epochs. Because water canniot be produced and like fossil fuel is a finite resource, it is at the point of its origins and crucial conduits- such as the Sutlej-beas confluence- that capital takes control.

In the 1990’s a period characterized by an exponential rise increase in the commodification of water and the emergence of water markets, we witness a dramatic shift in water distribution patterns globally. Nowhere was any other decade comparable to this in terms of prevailing water scarcities and pure thirst driving human beings like cattle. As capitalism further takes over managing the scarcities in terms of commodity values, what is referred to as ‘Conquest of Water’ (J Goubert) will remain a recurring them nightmare shaking human societies to their roots.

Our visit to Harikke made us acknowledge and understand the significance and importance of the singular position of water, the power vested in its control and ownership in the irrigated green revolution tracts of the ‘canal colonies’ of Punjab and the IGNP command areas of Rajasthan. It made us understand the growing importance of water, per se, in the shaping the strategies for interventions from above; its determining and defining nature vis-à-vis land and crops and it role in managing the economies of scarcity and waste. It is therefore in the interests of the producers and cultivators in these areas that alternative strategies that reduce dependence and overuse

of this critical resource be devised. For that is the only way to keep the struggles being fought at meaningful levels as well as continue with the resistance through democratic formats. Otherwise, to pre-empt democratic debates and formats or not attempt to produce rival future scenarios would contribute to leave things the workings of the market (which reflects the needs of those living but not the future generations) a suicidal prospect which many already face.

of this critical resource be devised. For that is the only way to keep the struggles being fought at meaningful levels as well as continue with the resistance through democratic formats. Otherwise, to pre-empt democratic debates and formats or not attempt to produce rival future scenarios would contribute to leave things the workings of the market (which reflects the needs of those living but not the future generations) a suicidal prospect which many already face.By Dr. Debabrata Banerjee

This article first appeared in Bulletin, July 2001, Vol 1. Bulletin was a newsletter of Chak Samities of the IGNP Stage II supported by AZERC, URMUL Trust and Oxfam

Tuesday, September 2, 2008

Consultation on Bio Diversity Strategy for Rajasthan

Before talking about the proceedings of the consultation in

To begin with, I must say that the Document is hardly a strategy and much less an action plan- it has no defined objectives in any time fame. It does not mention the actors involved (or to be involved in the execution of this strategy) except the omnipresent state (whose workings and understanding are problematic in many ways). One major flaw in the Document is that it completely ignores and bypasses the different communities or any other forms of associations that are responsible for conserving and using the bio-diversity of the Thar. Now whether that omission is deliberate or is an act of ignorance, RIPA only would know better. The there is no differentiation made between bio diversity use by the desert communities and by the industry. Following this the issue of control over natural resources is alluded to in a highly simplistic manner. We are living at living in the 21st century and surely a more complex mentioning of the interplay of the various institutions of the state, industry, different communities and classes in the society would have furthered our understanding of the use, control and regeneration of the bio diversity of the Thar. The kind of ‘state’ that comes out in the RIPA Document is very idyllic, pristine and smacks of an historical anachronism of mistaking it to be like the ancient state.

The whole issue of bio diversity conservation also is a moral and ethical enquiry – we are dealing with the de-sacralization of nature and commercialization of natural resources. In this regard, we, in a Third world country like

There is no mention of pastoralism especially as it is understood and practiced by different communities living in the Thar. Only on p.7 there is a reference to the issue of ‘reducing grazing pressure’ and ‘livestock breed improvement’. Surely RIPA needs to educate itself on this. Several new studies and field research by different people and agencies in

The coming in of the IGNP canal has been possibly the greatest change introduced in the bin diversity and ecology of the Thar in the last quarter of the 20t century. The Document does not suggest any particular measures understand and address the drastic changes. There is a mention of the concerns about IGNP on p’9 ‘developing informed policies a nd guidelines’ for ‘checking’ and ‘monitoring’ ecological changes. For a project that has deeply changed the very notions of bio diversity resource use and conservation held by the communities, this is a very mild consolatory gesture indeed!

nd guidelines’ for ‘checking’ and ‘monitoring’ ecological changes. For a project that has deeply changed the very notions of bio diversity resource use and conservation held by the communities, this is a very mild consolatory gesture indeed!

To sum up, it has been tried to put everything in the Document. The Document lacks a clear focus, a defined purpose. As it stands the Document needs to be narrowed to a few specific rubrics based solely on the criteria of ‘management’. The question of bio diversity is not as prominent as it is made out to be since most of it is already known. However bio piracy is in need of more attention and demands greater resistance from people who are gravely imperiled and disturbed. Instead of opening up bio reserves to huge bio technological firms for appropriation, intensive public advocacy is the need of the hour. Rajasthan RIPA can surely take this up in earnest.

The Consultation organized by Oxfam was an opportunity for NGOs in western Rajasthan to at least become aware of what is transpiring at the state level on an issue as crucial as bio diversity conservation and protection.

The IRDP programme of Oxfam and the partner NGOs in the Thar deals with issues of natural resource use and livelihoods of vulnerable groups. How to devise strategies for long term consolidation / drought proofing and to avoid relapsing into emergency drought relief year after year has been the defining philosophy for Oxfam, so told Savio Carvalho, the Oxfam programme manager.

In the consultation the first half was a kind of monologue- a display of scientific rhetoric marshaled by RIPA. In the presentations of various scientists, what was interesting was that they very rarely would refer to the active role of the different desert communities in preservation of the rich and unique bio-diversity of the Thar. The presentations done with all the modern gadgetry of laptops, slides, visual display of multi colour charts and photographs emphasized the ‘uniqueness of the Eco-System of the Thar’ as compared to the other arid regions of the world. What was also mentioned though in passing was the fact that the Indian Thar has had the longest and most populous human history. But the implications of this long and pervasive human presence for the use, loss and conservation of bio- diversity were issues not really dwelt on by any of the speakers. What was really appalling and surprising was that there was practically no discussion about the role of bio technology, issues linked to bio-piracy vis-à-vis bio-diversity and its conservation / protection. In fact one of the scientists lamented on the poor and backward state of knowledge, about bio-technology in particular, amongst the scientific community in Rajasthan.

In the second half there were presentations by two NOG / CBO representatives. Both of them talked about the catastrophic changes coming in the relation of the communities with the bio – diversity. Chatar singh talked about the diminishing grasslands in the Ramgarh (Jaisalmer) area. These grasslands still represent one of the finest specimens of bio diversity in the Thar and there is an urgent need for giving them proper protection. Madhavan talked about the concerns of erratic productivity, loss of older resource base strategies and the predominance of market based seeds as well as manures. All this in a context in which prices of a gricultural produce have become uncertain is creating a very precarious set of conditions for communities surviving in the Thar.

gricultural produce have become uncertain is creating a very precarious set of conditions for communities surviving in the Thar.

In the last session that was an open house, it came out quite clearly that there have been many gaps in the consultative process adopted by RIPA assured that they would correct this before getting down to any kind of further validation from the Document. The meeting ended with an assurance by RIPA to circulate the Document in Hindi and begin a dialogue.

The NGO representative had come to the consultation with a mix of set of feelings. The field NGOs are used to taking these kind of consultations with apathy and indifference, for something very rarely comes out of these big events. For some participating in them is just like a ritual. Yet there are some who come to these meetings with some hope in the future for the communities. The issue of protecting and conserving bio diversity in the Thar actually is not a new one and definitely has a lot of significance for the livelihood and survival of communities in Thar today.

This consultation was organized by Oxfam & NBSAP (GoI), RIPA (GoR),

This article appeared in Drishtikon, A Newsletter on Livelihoods and Advocacy, AZERC, URMUL Trust & IRDP Oxfam, November 2002

6 PM in the evening

flecting sunlight in all its resplendence. Traveling north-west of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan suddenly one come across a hutment surrounded by a carpet of yellow-gray shrubs clothing the surface. In the heart of

flecting sunlight in all its resplendence. Traveling north-west of Jaisalmer in Rajasthan suddenly one come across a hutment surrounded by a carpet of yellow-gray shrubs clothing the surface. In the heart of  ild animals, it is goats who bleat giving warning sounds of the danger. The rate of mortality among the sheep is much higher than goats in a scarcity period. It is a common saying that during scarcity the camel will eat everything but the Toomba (Caloptropis) but the goat eat that as well and leave only pebbles. This implies that the goats can survive on the scantiest of vegetation. Blaming the goat for the vast destruction of the grasslands may not be very realistic.

ild animals, it is goats who bleat giving warning sounds of the danger. The rate of mortality among the sheep is much higher than goats in a scarcity period. It is a common saying that during scarcity the camel will eat everything but the Toomba (Caloptropis) but the goat eat that as well and leave only pebbles. This implies that the goats can survive on the scantiest of vegetation. Blaming the goat for the vast destruction of the grasslands may not be very realistic.Embroidery Crafts of Thar, Western India

The article first appeared in Quilter’s Review, 32, Winter 2001, UK

In the arid regions of Gujarat and Rajasthan in western India there is a wide diversity of embroidery traditions. This is related to the ethnic differences of the population and the region’s strategic location at the cross roads of the great trade routes to the Arabian peninsula. Embroidery here is referred to as bharat, literally meaning ‘to fill’. It has traditionally enjoyed the status of hobby or pastime for wom

en as a coveted and precious display in the dowry package. Groups such as Rabaris, Ahirs, Rajputs, Meghwals / Harijan, Mutwas have rich and diversified embroidery traditions, though many of these groups have a marginal status in the rigid caste based society. This article will explain how embroidery has developed from a leisure activity destined for the dowry into a positive livelihood option, with the help of various Government and Non-Government agencies (NGOs). In the process the self confidence of the women has improved and their status increased.

en as a coveted and precious display in the dowry package. Groups such as Rabaris, Ahirs, Rajputs, Meghwals / Harijan, Mutwas have rich and diversified embroidery traditions, though many of these groups have a marginal status in the rigid caste based society. This article will explain how embroidery has developed from a leisure activity destined for the dowry into a positive livelihood option, with the help of various Government and Non-Government agencies (NGOs). In the process the self confidence of the women has improved and their status increased.

This process has to be set against the reality of life in these desert and semi-desert areas. The persistent droughts of the last three years and the earthquake in Bhuj in 2001 have been testing times, in particular. The desert and its fringes bear a fragile eco-system, which have lately suffered from the pressures of the growing population and exploitative government policies. Traditionally, some form of semi nomadic animal husbandry has been the most popular livelihood. Many communities are at various stages of adopting to a more settled lifestyle, but drought conditions make it impossible to rely on agriculture which depends on rainfall. The men are thus mostly unemployed. Marginal groups, including the women, often migrate seasonally away from their homes looking for labour. In these grim conditions, embroidery emerges as one of the most promising livelihood options, especially for the poor.

This has been helped by a growing market for handicrafts and ethnic items, nationally and internationally. The ‘hippie culture’ from the west has been particularly influential. In India itself, the emerging second generation middle class is looking to it roots and has initiated a wave of revival of all that is ‘traditional’.

In the 1970s, following the 1971 Indo-Pak war there was a mass exodus of people from Pakistan to Kutch and Barmer and Jaisalmer in western Rajasthan. This settlement of the Pak Osutees contributed to a dissemination of embroidery traditions among the local population. However, opportunists cashed in on the destitute situation of the refugees by buying their embroidered articles in distress sales and then selling them in cities for much higher profits. Market practices led to the formulation of this practice as ‘trade’. Production centres spread laterally to the nook and corners of the interiors of Thar to cater to this rising demand. The lack of any other promising source of income, the insecurity of settling into a new region, the pressures of raising a large family, the chronic unemployment of all the men led the women to succumb to the exploitative offers of the middlemen.

The middlemen were members of local communities who graduated to the status of big traders. The wages of women however remained the same year after year. They were merely casual wage labourers. They had to work all day and by lamplight in the night to earn the bare minimum for their households. Often they had to put up with payments in kind from the middlemen’s grocery shop in the village. Working conditions were so poor that very soon bharat became known as dukhi bharat, embroidery impregnated with sorrow. Though the women, and the men too, were aware of the exploitative nature of the trade, they never tried to demand more for the fear of loosing this only means of livelihood. A major portion of Kutch in Gujarat and Barmer, Jaisalmer and Bikaner in Raja

sthan were active grass root centres of this chain of mass production.

sthan were active grass root centres of this chain of mass production.

Mass production meant that everything from raw materials to design motifs was decided for the craftswomen, reducing their status from a creator to a mere producer of labour intensive embroidery. This had a devastating effect on traditional embroidery skills. Often the quakity of raw materials used to be poor- untwisted silk floss and mirror instead of glass. Embroidery patterns were crudely printed. A selected few designs were used repeatedly and quality work was not appreciated. The women did mange to continue thewir own traditional embroidery, but at a mucxh lower scale and intensity.

The intervention of different NGOs like SEWA, URMUL, SURE, Kalarakasa aimed to improve their lives and status of women in these areas. Some also addressed the basic issues of health, education and others sought to initiate a process of social empowerment through bharat. The aim was to lift the status of craftswomen from casual wage labourers to dignified artisans. The middlemen had been interested in the ‘traditionally’ embroidered product. In contrast to that the NGOs focused on the lives of woen with traditional skills. Their income generation programmes set out to preserve and continue locals craft traditions and maximize the wages of women allowing them to be creators rather than being mere producers. Women were facilitated to form groups as independent entrepreneurs. Through this enhanced ability at income generation the owmen also were regarded with more dignity, they felt socially empowered.

The NGOs earned the trust of local people by aiming to improve their quality of life, rather than making money out of them. They seek to promote self sufficiency, beginning with intensive training to improve skills and help them understand the quality required by the market. Groups are taught to save money and they can access capital loans at minimal interest rates to initiate and mange their own production. The NGOs assist with design and marketing and encourage women to make their own design and finance decisions. They are invited to directly participate in lot of exhibitions in different cities in India and even abroad. This gives them a better idea of the market, and of consumer tastes and lifestyle.

The NGOs aim to achieve a balance between the market driven strategy of a business initiative and the free expression of a women embroiderer. They have largely succeeded in upgrading skills, improving quality and workmanship and keeping production closer to tradition. The women have the self confidence to realize their worth as contributors to their family incomes and as bearers of a rich embroidery tradition. Faith in their won tradition has gro

wn deeper.

wn deeper.

The NGOs plan to phase out in 8-10 years, by which time it is hoped that the women group is self sufficient. Some have achieved this. However, continued success depends up in keeping up with changing conditions. Some NGOs have been sluggish in adapting to fast changing market trends, leading to large quantities of dump stocks and the continued for outside funds for support. May be the system need a restructuring to cope with the new challenges of a liberalized market environment.

Embroidery (Bharat) traditions and women casual labour in Barmer, Rajasthan

This article is a short account of the changes in the livelihoods of the war displaced women who came to India after the Indo-Pak War from the villages of Thar parkar, the district of lower Sind contiguous to Rajasthan and Gujarat. The aftermath of the war was followed by an exodus of around three lakh people (around 90,000 families) to the districts of Barmer and Jaisalmer in Rajasthan alone.

Thars fled from their villages for the fear of persecution, hardship and discrimination at the hands of the military dictatorship of the Islamic state of Pakistan as well as the uncertainties and scarcity of the war affected and occupied territory. The hopes for a better future in India eroded soon in the face of the growing hostility of the raiyas (natives) on the Indian side of the border as well as by the align and partisan treatment meted out by the Indian state. Viewed with suspicion they were doomed to exist as sharanarthis (refugees) dependent upon the rations provided by the Indian state in relief camps under confinement and strict surveillance. These rations could barely sustain them and a struggle for survival relied more on the deployment of coping strategies. These coping strategies were subaltern practices evolved by the sharanarthis themselves in response not only to an indignant native population but an equally hostile harsh climate of the arid region of western Rajasthan.

Thars fled from their villages for the fear of persecution, hardship and discrimination at the hands of the military dictatorship of the Islamic state of Pakistan as well as the uncertainties and scarcity of the war affected and occupied territory. The hopes for a better future in India eroded soon in the face of the growing hostility of the raiyas (natives) on the Indian side of the border as well as by the align and partisan treatment meted out by the Indian state. Viewed with suspicion they were doomed to exist as sharanarthis (refugees) dependent upon the rations provided by the Indian state in relief camps under confinement and strict surveillance. These rations could barely sustain them and a struggle for survival relied more on the deployment of coping strategies. These coping strategies were subaltern practices evolved by the sharanarthis themselves in response not only to an indignant native population but an equally hostile harsh climate of the arid region of western Rajasthan.One such coping strategy employed by the women of the Pak Oustees was the reworking of the female handicraft traditions for market production. The years of survival in the camps and the decade after has seen the commodification of these once domestic handicraft traditions. The life of limited opportunities, the marginalization of male traditions of weaving, and increased incidence of alcoholism at a time when women became producers for the big market of handicrafts contributed to the reordering of the gender space within the households. In the pages to follow an attempt is made to delineate the stages of the ‘fetishisation” of the exquisite art/ craft of embroidery (bharat) traditions in the context of the emergence of a large women causal labour force in the Barmer district of Rajasthan.

Craft traditions from the west

The Thar parkar, especially its arid tracts, contiguous with those in India had a rich diversity of craf

t traditions practiced by both men and women. The slow and idyllic life of the arid tracts with leisure time at hand and proliferation of settlements as well as occasions of exchange was particularly well suited to the proliferation of these craft traditions. Mirror work incorporated with thread work originated with the use of mica found in the desert. In this account the discussion is restricted to craft traditions known as bharat (which literally means to fill) in the local dialect and includes both embroidery as well as appliqué / patchwork traditions. Oral testimonies of Dhatis, the natives of Thar Parkar, do not say anything definite about the exact place of origin of these traditions. However most accounts point out that the traditions came from the West, from the vast chain of Persio-Arabian deserts stretching uninterruptedly across the entire width of the Near East. The route to Thar Parkar lay via the tract known as Sawloti (comprising of Mithi and Diplo taluka) which can be easily designated as the nucleus of these craft traditions. It was from this core that the traditions diffused eastward towards Chachro and Nagar Parkar talukas. Given the demographic composition of these tracts it would not be too far fetched to surmise that the initial bearers of these traditions must have been several nomadic pastoral groups like the Baloch.

t traditions practiced by both men and women. The slow and idyllic life of the arid tracts with leisure time at hand and proliferation of settlements as well as occasions of exchange was particularly well suited to the proliferation of these craft traditions. Mirror work incorporated with thread work originated with the use of mica found in the desert. In this account the discussion is restricted to craft traditions known as bharat (which literally means to fill) in the local dialect and includes both embroidery as well as appliqué / patchwork traditions. Oral testimonies of Dhatis, the natives of Thar Parkar, do not say anything definite about the exact place of origin of these traditions. However most accounts point out that the traditions came from the West, from the vast chain of Persio-Arabian deserts stretching uninterruptedly across the entire width of the Near East. The route to Thar Parkar lay via the tract known as Sawloti (comprising of Mithi and Diplo taluka) which can be easily designated as the nucleus of these craft traditions. It was from this core that the traditions diffused eastward towards Chachro and Nagar Parkar talukas. Given the demographic composition of these tracts it would not be too far fetched to surmise that the initial bearers of these traditions must have been several nomadic pastoral groups like the Baloch.When and how these pastoral traditions were adopted by the Hindu in the Thar Parkar is something on which the accounts do not say anything definitive. But what is peculiar about the assimilations of the bharat traditions is their popularity and provenance amongst the subaltern groups. The practice of wearing embroidery was more prevalent among the lower castes like the Meghwals, Ravana Rajputs, Bhils and Kolis. In fact many elders remembering life in the Thar Parkar remark “…wearing bharat was a stigma, a mark of being low caste, of placing and identifying a dhend as the Meghwals were derogatively addressed.”

Traditions of exchange and Communication

The bharat traditions were household traditions and were personalized expressions of a gift economy. Each embroidered piece was an individualized expression of the female artisan’s passion and love for her family members and relatives. The desire to embroider may be explained as an urge to add embellishment to cloth, the desire to bring colour, design, vivacity and an identity to something which is plain and austere. The elderly women in the community initiated the young girls into this craft at the early age of six or seven. The initiation into the production of craft was part of the larger process of socialization of the neophytes. By the time the girls were married they had a collection of different bharat to decorate their own new homes and thus display their embroidering skills to the relatives.

If we stroll through the gallery of objects which were produced under the rubric bharat we would see how the fantastic range of the domestic tradition was meant to engulf (rather fill) almost every aspect of the life of the per

son to whom it was gifted. This is what constituted bharat as one of the most memorable gifts, almost as important as the jewels exchanged on ceremonial occasions. A glance through the typical dress code of the bride and groom of the lower caste in Thar Parkar would suffice as an illustration. Conventionally the male attire decorated with bharat would include a rumal (handkerchief), a kadbandhna, a safa (turban), a topi (cap), a malir while the bharat adorned female dresses like the odana (veil), kanchli (bodice), kanjri and ghaghra (skirt). Apart from these dresses bharat included objects like raali, seranthio, pagothia, gadadi, thelo (bag) even mojadi (shoes). The intricate geometrical designs, symmetrical placing of squares, triangles, circles all embroidered through a variety of stitching practices like kutcha, soof, kharak, mucca, jari, etc using attractive colour schemes are suggestive of the fact that bharat ranked as one of the fairly well developed handicraft traditions of Thar parkar. The designs told a story or served a need, patterns brought harmony and the colours imparted character which stood out in the sandy and monotonous landscape of the desert.

son to whom it was gifted. This is what constituted bharat as one of the most memorable gifts, almost as important as the jewels exchanged on ceremonial occasions. A glance through the typical dress code of the bride and groom of the lower caste in Thar Parkar would suffice as an illustration. Conventionally the male attire decorated with bharat would include a rumal (handkerchief), a kadbandhna, a safa (turban), a topi (cap), a malir while the bharat adorned female dresses like the odana (veil), kanchli (bodice), kanjri and ghaghra (skirt). Apart from these dresses bharat included objects like raali, seranthio, pagothia, gadadi, thelo (bag) even mojadi (shoes). The intricate geometrical designs, symmetrical placing of squares, triangles, circles all embroidered through a variety of stitching practices like kutcha, soof, kharak, mucca, jari, etc using attractive colour schemes are suggestive of the fact that bharat ranked as one of the fairly well developed handicraft traditions of Thar parkar. The designs told a story or served a need, patterns brought harmony and the colours imparted character which stood out in the sandy and monotonous landscape of the desert.These presentations of what a cultural anthropologist has aptly called ‘threads of life” were communicative skills par excellence. It is through the production of these, during times of leisure or timed to climax with a significant ritual or rites of passage, that the women communicated with nature as well as the world around them. Many names of the designs like sugga (parrot), nimbodi (of the neem tree), bachda (calf), kambhiri, bawalia, kurja, lehrio (wavy), etc are suggestive of this. It may be interesting to note that there are folk songs which are referred to by similar names as these desig

ns thus conveying their important place in the oral folk tradition. The repertoire of patterns was fairly vast and consisted of hundreds of designs. Even in the case of patchwork, more popular among the Rajput and Charan women, the different figurines and animals cut in varying sizes to be placed in a particular order on the sheet of cloth signified their image of the world / nature.

ns thus conveying their important place in the oral folk tradition. The repertoire of patterns was fairly vast and consisted of hundreds of designs. Even in the case of patchwork, more popular among the Rajput and Charan women, the different figurines and animals cut in varying sizes to be placed in a particular order on the sheet of cloth signified their image of the world / nature.It was this kind of domestic craft tradition serving a gift economy of prestige and love which the Dhati (driven away) women brought along with them when they left their houses for fear of persecution, injury or death. The visual expressions of women and the artisans themselves, embedded in a pre-literate rural culture, were to undergo a radical transformation in the ensuring years of survival as sharanarthis, in a struggle to escape from penury, destitution and famine.

Handicraft Boom and Struggle for Survival

In the early months of 1972, in their struggle to eke out an existence in India, the Pak Oustees discovered that the bharat which many of them had managed to get along with them was in demand in the handicraft bazaar of Barmer city. Distress sale of bharat along with other valuables at throw away prices was one of the widely practiced coping strategies. The villages of Chohtan and Sheo tehsils (blocks) wee suddenly flooded with a large number of artisan women who could be made to work in meager sums. The handicraft traders of Barmer had stuck a fortune. The camps were targeted as sites of mass production of bharat. The trader would supply the necessary raw material to the women sitting in the camps and collect from them exquisite finished products often paying miserably low rates like one rupee for sticking ten mirrors in a cap or five rupees for embroidering a cushion cover. The early seventies saw the emergence of some big traders who were to dominate the trade in handicraft in the coming years. The handicraft trade with the twenty five relief camps was controlled by two main traders- Pitambar Das Shishopal located in Gadra monopolized villages in Sheo tehsil and Asulal Dosi located in Chohtan tehsil monopolized production in all its villages. By the end of seventies both these firms had grown into large export houses with showrooms in Jodhpur and Jaipur with annual turnovers of more than 10 crores. The ghettos like Leladi Dhora in the city of Barmer were left for local traders from Barmer city. These local traders had their own clientele of outsiders, mainly working in the armed forces and other Government jobs who numbers increased substantially.

Years of hardships in relief camps transformed the relations of Dhati women with these craft traditions. From expressions of desire, affection and exchange bharat became products highly valued added and produced exclusively for the growing market abroad. The connectedness between artisan and bharat was replaced by a wage in cash relationship. The growing alienation between the worker and her product also manifested itself in a new rationale for production-instead of being made for special occasions or periods of liminal transition, th

e production of baharat was regulated by the whims and orders of a merchant. This mass production for the handicraft market rested on the immobility of the women labour force. It was sustained by the logic of confinement implicit in the life in the refugee camps, and the social and cultural taboos which debarred women from venturing into the public sphere. The production and marketing process was hierarchical in which a handful of big merchants were at the top followed by a large number of consisting mostly of Pak Oustee males with the artisan women at the lowest rung. The big merchant would advance raw material which was to be carried by the middlemen to the artisans sitting in the villages. Usually one such middlemen would be entrusted with 8-10 villages. Often there were a number of commission agents between the middlemen and the artisans who in turn would monior the production in one village or a cluster of houses. Sometimes this chain that worked like pre-capitalist putting out system could have as many as eight middlemen between the merchant who invested the capital and the bharat artisan who made the product. Wages, which were as such depressed, accruing to the artisan women were further lowered by the commissions of each such middlemen.

e production of baharat was regulated by the whims and orders of a merchant. This mass production for the handicraft market rested on the immobility of the women labour force. It was sustained by the logic of confinement implicit in the life in the refugee camps, and the social and cultural taboos which debarred women from venturing into the public sphere. The production and marketing process was hierarchical in which a handful of big merchants were at the top followed by a large number of consisting mostly of Pak Oustee males with the artisan women at the lowest rung. The big merchant would advance raw material which was to be carried by the middlemen to the artisans sitting in the villages. Usually one such middlemen would be entrusted with 8-10 villages. Often there were a number of commission agents between the middlemen and the artisans who in turn would monior the production in one village or a cluster of houses. Sometimes this chain that worked like pre-capitalist putting out system could have as many as eight middlemen between the merchant who invested the capital and the bharat artisan who made the product. Wages, which were as such depressed, accruing to the artisan women were further lowered by the commissions of each such middlemen. By the time the relief camps ended in 1979-80, the production processes were well entrenched and operating in the villages of Chohtan and Sheo. The handicraft boom thst came riding on the romantic constructions of Thar had managed to carve out a space for itself in the informal sector of a rural economy of barmer district. Thus, bharat, a tradtion from the other side of the border, and practiced by women artisans from war displaced families were gradually integrated into the lowest rungs of the rural society of barmer district.

Immiserisation and Wage Hunting

The consecutive famines in the eighties put further squeeze on the household economies of the barmer district. The sudden closure of refugee camps and an absence of any opportunities for employment complelled more and more women to seek recourse to the production of bharat, even at depressed wages, as the only alternative. The scarcity of food fodder nd water affected the raiya populations as well. Consequebntly many women from other castes even amongst the riaya got drawn into this un-regulated non-agrarian sector of the economy of the frontier district. This expansion of the female labour force had its own impact on the on-going commodification of bharat traditions. The market oriented production adjusted itself to tap this easily available and cheap labour force by introducing

certain changes in the strategies of production. The emphasis was on simplifying the products often at the expense of quality as well as the exquisiteness and complexity that had been the hallmark of bharat traditions.

certain changes in the strategies of production. The emphasis was on simplifying the products often at the expense of quality as well as the exquisiteness and complexity that had been the hallmark of bharat traditions.The employment of raiya women who were not the original bharat artisans favored the patchwork traditions more. Unlike embroidery, which was labor intensive and required skilled labor, the advantage with patchwork was that it involved the relatively simpler tasks of cutting figurines and placing them. It was also easier to replicate the patchwork traditions as the figurines could be cut in large numbers using a cutting machine which made it a more suitable product for mass production. In embroidery the more complex patterns using complicated stitching practices like kharak were abandoned in the favor of a new set of designs which were easier to execute. That the ‘age of creation’ was on

the wane could be discerned in the popularity of new designs like the village scene, half moon, Taj Mahal, Ganga, Sea, desert life etc. These new designs, as the names suggest, had little to do with the creative urges of the bharat artisan and emphasized mass production for an alien market. Through the mass production of such new designs the bharat traditions were making a transition to the ‘age of mechanical reproduction’.

the wane could be discerned in the popularity of new designs like the village scene, half moon, Taj Mahal, Ganga, Sea, desert life etc. These new designs, as the names suggest, had little to do with the creative urges of the bharat artisan and emphasized mass production for an alien market. Through the mass production of such new designs the bharat traditions were making a transition to the ‘age of mechanical reproduction’. The enlargement of the informal sector manifested itself through changes in the constitution of the production chains. The small number of middlemen who were pioneers in venturing out into trade in the seventies gave way to more of their kind as they scaled up further to become petty organizers of production for increased profits. The eighties were characterized by the emergence of these petty traders from amongst the Pak Oustee community who often worked with capital advance by the giants of the trade. This emerging hierarchy among the traders was accompanied by as growing differentiation in the strategies of tapping and regulating labour. For instance, the petty traders from the pak Oasutee community because of their grater rapport with the bharat artisans could convince women to come to their units thus saving on the expenses and worries of sending raw material and collecting finished products.

A case study on the expansion of such production units from a handful to more than thirty in a decade in the village of Dhanau points to the handicraft production emerging as one of major occupations of women in the rural economy. Most of the units which started in eighties were the initiatives of the Meghwals from the Pak Oustee community. These units in Dhanau tap women labor from around twenty five villages and dhanis in a radius of around 30 km. n spite of differences and stiff competition amongst these units they follow a common strategy of regulating bharat labour. All of them operate on a weekly basis with each Monday of the week marked out for cash transaction with women. This has tied women to a weekly cycle of oscillation between their households and these units. On Monday women from all around make their appearance, coming in groups of five or six. Dhanau on Monday is crowded by these ‘wage hunters’. The bharat artisans who were not tied to one particular unit deposit their finished products claim their wages then go to the different units, and pick up more raw material to work on.

The involvement of a female artisan in bharat production begins with her establishing a link to a production unit, mostly producing out of her household time along with dispensing her duties as a mother as well keeper of livestock. Most of her leisure tie is spent in bharat usually providing her an occasion to interact with other women from the same settlement. The job done consistently and diligently over along period of time very often results in excessive strain on the eyes. Partaking of boric acid or snuff as antidotes to this are fairly common among the older women workers. In the absence of nay other source of employment these women work round the year producing bharat in weekly or fortnightly cycles. Time off from this impinging rhythm of production is literally dependent on the good fortune and nature’s benevolence. If it rains well for seven to eight days (which is rare and happens only once in many years) in July-August then they work as farmhands for around a fortnight sowing their fields and about the same number of days in October-November when they harvest the subsistence grains.

The commodification of bharat traditions over the last quarter of the century has situated the bharat artisans as possibly the largest group among the women wage workers in the laboring landscape of Barmer. This swelling of the number of women wage hunters and gatherers’ has had an adverse effect on their wages which on the average vary between Rs. 200-5000 per month to as low as Rs. 15-20 per month. The payment in cash is many times supplemented or replaced with wage advances in kind consisting of daily provisions from the village shops invariably owned by the middleman or the petty trader. These subsistence wages in kind unleash their own cycles of indebtedness which is another feature of the growing immiserisation of the primary producers of the exotic handicrafts. Thus the ‘fetishization’ of the bharat traditions continues unabated in a sector whose characteristic features are unrestrained capital and footloose and disenfranchised labour.

Photo Credits: Swasti Singh